Arrhythmia-Induced Cardiomyopathy: Key Points

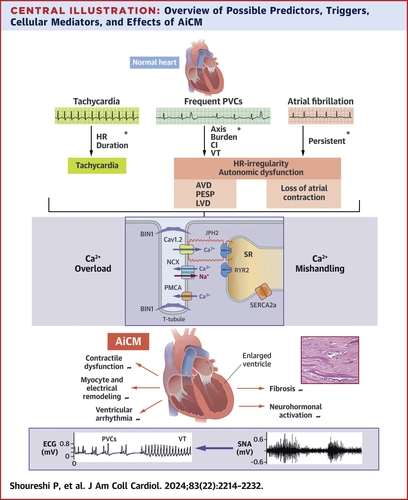

The following are key points to remember from a state-of-the-art review on arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy (AiCM):

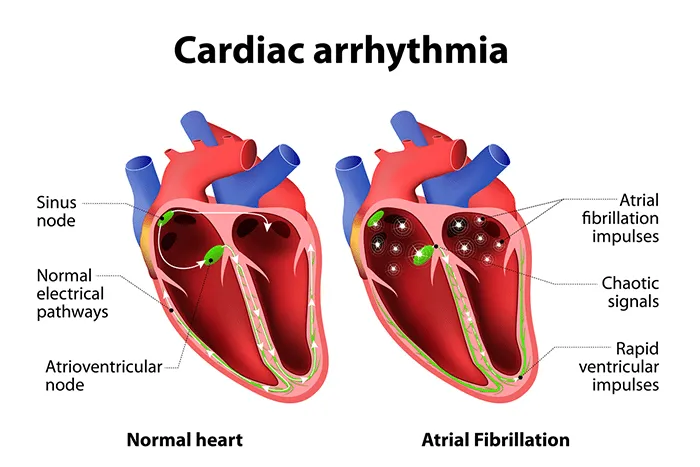

- AiCM encompasses tachycardia-induced CM (T-CM), atrial fibrillation–induced CM (AF-CM), and premature ventricular contraction (PVC)-induced CM (PVC-CM). This term does not include the more recently recognized forms of CM resulting from abnormalities in the conduction system, such as chronic right ventricular (RV) pacing, left bundle branch block, and cardiac pre-excitation.

Tachycardia-Induced Cardiomyopathy

Etiology

- AF and atrial flutter with rapid ventricular response are the most common causes, but other arrhythmias also confer risk: atrial tachycardia, atrioventricular (AV) reciprocating tachycardia, AV nodal re-entrant tachycardia, sustained sinus tachycardia, various ventricular tachycardia (VT), and pacemaker-mediated tachycardia.

Pathophysiology and Mechanism

- Animal models of sustained, continuous atrial pacing typically show biventricular dilatation without hypertrophy or change in heart mass, but with mild ventricular thinning.

- There are structural and functional myocardial changes, along with electrical and calcium remodeling, resulting in impaired excitation-contraction coupling and diastolic dysfunction.

- Four weeks after discontinuation of tachy-pacing, Ca2+ transients, Ca2+ uptake, and creatine kinase activity have significant normalization, whereas fibrosis persists despite normalization of left ventricular (LV) function.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- The development of T-CM in clinical studies occurred between 3 to 120 days from the onset of tachycardia.

- Using an ambulatory ECG monitor for ≥2 weeks is essential to establish the T-CM diagnosis.

- T-CM is characterized by a dilated CM with moderate to severe biventricular systolic dysfunction and lack of hypertrophy. Mitral insufficiency may be present.

- The definitive diagnosis of T-CM can only be established after recovery or improvement of LV systolic function within the first 6 months after eliminating the culprit tachycardia.

Treatment

- The primary treatment involves suppressing the primary arrhythmia using antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) or ablation. Initiating or optimizing heart failure (HF) medications is essential to promote reverse remodeling.

- LV function typically improves within 4-12 weeks, and HF symptoms often improve by ≥1 New York Heart Association (NYHA) class in most patients.

- Full recovery of T-CM is not always achieved, and specific histopathologic abnormalities, diastolic dysfunction, and ventricular dilatation with hypertrophy may persist despite normalizing LV systolic function.

- Permanent treatment of tachycardia with ablation is especially helpful for arrhythmias with a high success or cure rate, such as atrial flutter, AV nodal re-entrant tachycardia, AV reciprocating tachycardia, and atrial tachycardia.

AF-Induced Cardiomyopathy

- Rate control is the key to distinguish between AF-CM from T-CM.

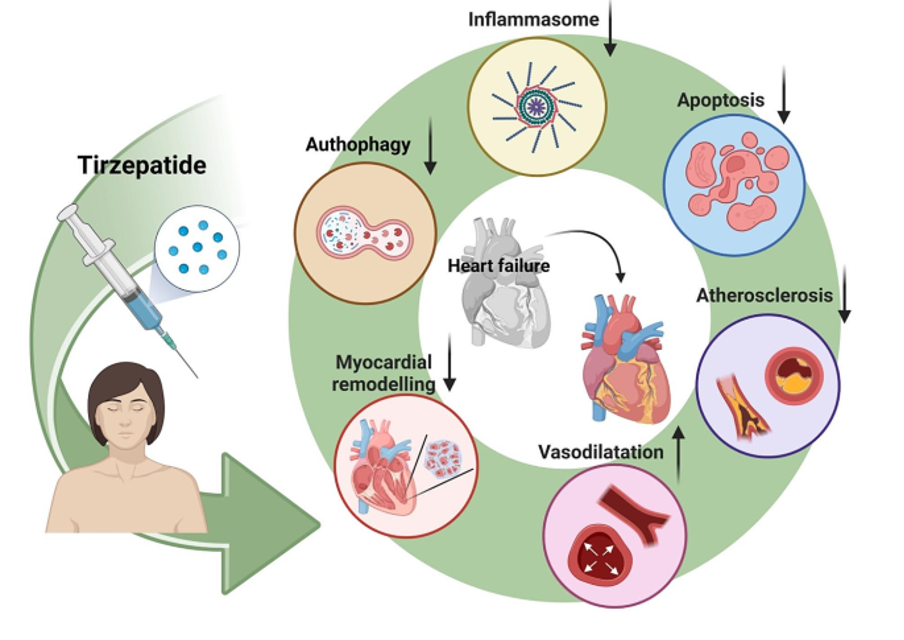

- The mechanism underlying AF-CM is believed to be triggered by irregular heart rate leading to abnormal Ca2+ dynamics; and loss of atrial contractility and emptying, which ultimately triggers sympathetic activation.

- Patients with AV nodal ablation plus biventricular pacing have clinical benefits when compared to patients with a similar degree of rate control.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- AF-CM is diagnosed after exclusion of other etiologies and should be suspected primarily in patients with nonischemic CM and persistent AF, where there is no improvement despite appropriate medical therapy and rate control.

- A conclusive diagnosis of AF-CM can only be confirmed if LV systolic function improves or returns to normal after AF elimination.

Treatment

- The clinical management of AF-CM includes guideline-directed medical therapy and rhythm control.

- The current evidence suggests that ventricular rate control alone during AF may not reliably predict CM reversibility.

- AF ablation can maintain sinus rhythm in 50-88% of patients with HF and CM. In the CABANA trial, catheter ablation improved survival, freedom from AF recurrence, and overall quality of life when compared to drug therapy.

- AADs have an overall success rate of 30-50% in maintaining sinus rhythm. Landmark AF trials with AADs have not shown significant benefits in outcomes, including HF admissions, in patients with or without HF or CM.

PVC-Induced Cardiomyopathy

- PVC-CM is characterized by the development of LV dysfunction attributed only to frequent PVCs.

- Superimposed PVC-CM can be described as a deterioration of LV ejection fraction of ≥10%, resulting from frequent PVCs in a previously diagnosed CM.

Epidemiology of PVCs and PVC-CM

- PVC prevalence is higher with age, especially in those ≥75 years. PVCs are often linked to post-myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, dilated CM, and HF with reported prevalence above 90%.

- PVCs are an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

- There is a robust correlation between high PVC burden and LV.

- Frequent PVCs are a significant but modifiable risk factor for systolic HF and elevated mortality.

Potential Mechanism(s) of PVC-CM

- The primary cause of contractile dysfunction is related to disruptions in the Ca2+-induced Ca2+release mechanism. PVCs disrupt cardiac autonomic balance leading to chronic imbalanced sympathetic overload. PVCs with variable coupling intervals appear to disrupt cardiac autonomic balance most potently.

- An animal study demonstrated that LV dyssynchrony and post-extrasystolic potentiation might contribute equally to the progression of PVC-CM.

Predictors of PVC-CM

- While some studies indicate that a PVC burden of ≥10% is required for the development of PVC-CM, other publications note LV function improvement at PVC burdens as low as 6-8%.

- Some patients with high PVC burden do not develop CM. Interpolated PVCs, PVC-QRS duration (>157 ms), and epicardial origin have been consistently found to predict PVC-CM.

Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Prognosis

- The timeline for PVC-CM development ranges from months to several years.

- PVC-CM should be suspected in patients with frequent PVCs (>10%), especially in nonischemic CM.

- A minimum of 6 days is ideal to detect an individual’s maximum PVC burden.

- PVC-CM is characterized by mild to moderate LV dysfunction, LV enlargement, mild mitral regurgitation, and left atrial enlargement, which typically resolves within 2-12 weeks after eliminating PVCs.

- The ABC-VT scoring system predicts adverse LV remodeling and future clinical outcomes in patients with frequent PVCs, incorporating factors such as superiorly directed PVC axis, PVC burden, PVC coupling interval >500 ms, and nonsustained VT.

Treatment

- The optimal PVC burden threshold for intervention is unclear. Guidelines recommend PVC suppression in patients with CM and PVC burden >15%.

- Patients with frequent PVCs (≥10% burden) without LV dysfunction, should be regularly monitored at least every 6-12 months.

- Both ablation and AAD therapies have exhibited similar long-term PVC suppression rates ranging from 70% to 80%.

- No randomized, prospective studies have directly compared ablation and AAD therapy outcomes.

- In a multicenter retrospective study, 67% of nonischemic CM patients with frequent PVCs (mean PVC burden 20%) showed LV function improvement after ablation.

- Successful ablation can restore RV function in patients with PVC-CM affecting the RV.

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging–assessed scar burden can predict responders and nonresponders to PVC suppression, especially when there is a substantial reduction (>20%) in PVC burden.