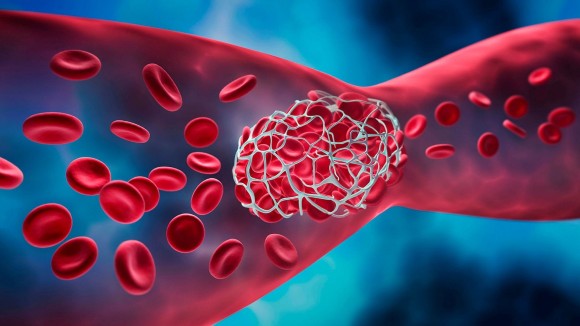

Antithrombotic Therapy in High Bleeding Risk for Noncardiac Interventions: Key Points

15 November 2024

The following are key points to remember from a state-of-the-art review on antithrombotic therapy in patients with high bleeding risk (HBR) noncardiac percutaneous interventions from the Working Group of Thrombosis of the Italian Society of Cardiology:

© 2022 Cardio Blogger. All Right Reserved | Designed & Developed By Diviants